Egypt’s Foreign Policy Paradox on the River Nile (First Published in 2014, still relevant)

|

| #Itsmydam |

One can boldly argue that

Egypt’s foreign policy orientation towards the Nile has always been proactive.

Given the determinants of foreign policy – ranging from the composition of

foreign policy decision-making units to the contemporary balance of power configuration

at the global or regional level – one can easily find as many variables as one

wishes to justify or defend the vigorous foreign policy orientation of the

Republic. Accordingly, Egypt has intensified diplomatic warfare against the

Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), aiming at neutralising many of

Ethiopia’s perceived allies and resurrecting the age-old fault lines to direct

considerable pressure on Ethiopia.

Egyptian foreign policy orientation emanates from the perception that the Nile River stretches beyond their geographic boundary.

Considering that 85pc of their population resides across the basin, the Nile River constitutes the cognitive behaviour of Egyptian foreign policymakers.

Generally, the prime objective of foreign policy for Egyptians

is to secure the uninterrupted flow of the water using whichever alternative is

possible. Their options include complete control of the basin, cooperative

diplomacy, threatening to use force and undermining the sovereignty of riparian

states, especially Ethiopia. Be this as it may, securing the waters from

potential threats has always been the centre of their foreign policy, while

securitisation remains its primary pillar.

If one is to go by the constructivist stance, a security issue

is a threat to the survival of a nation. Taking this stance, Egypt declared

that any interruption to the flow of water into the Aswan High Dam is an

existential threat to Egypt. It seems valid if one considers the Egyptian

situation alone.

A country whose average rainfall is close to zero and where

almost 85pc of the entire population resides in the basin is believed to do

anything possible to secure the only source of life – the Nile River. On the

other hands, agriculture, which uses 86pc of the available water, accounts for

only 14pc of Egypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) and Egypt imports more than

half of its food consumption annually, though it inefficiently uses the water.

Therefore, the securitisation of the Nile River by Egypt is mostly

a political process rather than a survivalist one. According to the

securitisation division of labour along the Nile Basin, Egypt securitises the

water and Ethiopia ‘de-securitises’. Accordingly, the 1959 agreement can best

be understood as the peculiar measure Egypt has taken to ensure its security,

forcing Ethiopia to re-write this agreement by the CFA.

Development of trans-boundary water resources has complexities

brought by tension in riparian relations and snags regarding institutional

arrangements. Dams, with all the criticisms against them, are the triumph of

human civilisations. They provide opportunities, such as energy to power

industries, irrigation to produce food and facilitate the growth and

development of cities even in deserts.

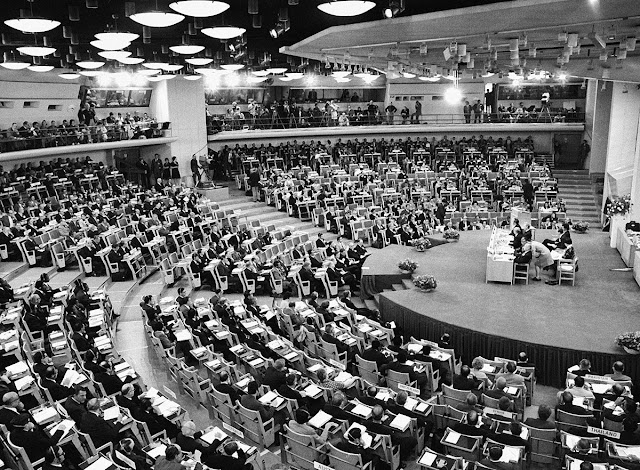

Dams are also symbols of national pride, as in the case of Aswan

High Dam of Egypt and the GERD of Ethiopia. President Nasser’s speech about the

Aswan High Dam in Egypt and the all-time resource mobilisation for the

GERD project in the Ethiopian case provides a vivid explanation for the above

assertion.

The GERD is hailed as the patron of the Growth &

Transformation Plan (GTP) in the Ethiopian context and the architect for

regional integration, as far as the Eastern Nile Basin is concerned. If David

Ricardo’s comparative advantage principle still rules global economics,

Ethiopia must engage in producing electricity, not only to supply energy for

its ever-growing economy but also to support its neighbours in solving their energy

insecurity (poverty). For instance, the energy insecurity in Egypt has forced

the government to allocate millions of dollars annually to electricity

production using petroleum, though it is still not adequate.

Despite many studies, indicating the full range of benefits,

downstream countries will obtain from GERD, Egypt, unlike Sudan, is waging

diplomatic warfare against the dam. This irrational behaviour of Egyptian

foreign policy can be explained by the nexus between regional and domestic

variables.

At the regional level, the self-portrayed ‘master of the Nile’ –

Egypt – has been trying to dominate the hydropolitics of the Nile Basin and

keep their perceived hegemony intact. The Aswan High Dam and the 1959 agreement

between Sudan and Egypt are the core measures Egypt took to sustain its

dominance over the basin. Consequently, Egypt opposes any development that they

think might erode its hegemony – even if it involves re-writing the

International Panel of Experts (IPoE) report, which Egypt signed by establishing

another panel of experts.

On the other hand, Egypt’s unfounded behaviour can be elucidated

based on how Egypt writes its identity through its national interest and vice

versa. In many cases, political identities are the ‘without sets’ of otherness.

Otherness makes boundaries visible.

Such difference over core matters entailing a conflict of

interests, such as the Nile River, increases the possibility of transforming

differences into a threat. Thus, a state’s survival as a primary unit in

contemporary international relations is determined by how effectively it

capitalises on discourses of danger and how it crafts its foreign policy to

serve this interest.

Governments feed on a discourse of threat to endure and rule,

and their foreign policy provides the means. Accordingly, consecutive Egyptian

governments lived on the discourse of threat they composed on the Nile River.

Given the current instability in the Egyptian Republic, the government may use

the Nile card to arouse as much discourse of threat as possible, to

direct the attention of Egyptians towards their political identity constructed

at the expense of Ethiopia.

It is palpable that Egypt will try to connect the GERD with

Israel and Turkey so that Egypt can get moral and financial support from the

Arab League countries. If one simply observes superficially, the Egyptian

strategy appears valid.

Will Egypt get the same moral and financial support as

Palestine?

No, they will not mainly because the Palestinian people are

fighting for their occupied territories given unjustly to Israel by the

British. The Ethiopian people are fighting for the ‘right to use the Nile

River’ given unfairly to Egypt by the British.

Egypt is Britain’s Israel in the Nile Basin. Therefore, it is

irrational, if not delusional, to expect countries with a reputation for

fighting injustice to fight for the other side.

Egypt must come to its senses and start to reconcile reality.

The GERD has benefits for all Nile Basin countries and the ‘old school’ that

has been promulgating unilateralism, and a desire to remain the ‘masters of the

Nile’ must give way to the ‘new school’ aiming at basin-wide cooperation –

energy cooperation, to be specific.

The future of energy cooperation relies on the ability to move

away from the traditional conception of foreign policy orientation that

resulted in the securitisation of relations along the Nile River towards

pragmatic reconciliation of the prevailing energy insecurity. Only then can the

riparian countries of the Nile River embrace energy cooperation. The Sudanese

have shown their readiness to cooperate on mutually benefiting projects, such

as the GERD.

Egypt, however, seems locked in traditional narratives of

dictating terms on matters of the Nile River under the disguise that Egypt is

nothing but the Nile.

Comments

Post a Comment